Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) Tools

What is DBT and how might it be helpful?

Ontarians and their families have faced difficult challenges over recent years. Many clients are curious about what DBT can offer to help them cope with the aftermath, find their ‘new normal’, or address their long-standing concerns. In short, DBT is a sister therapy to CBT, and involves practicing ‘Dialectical Thinking’, mindfulness, and interpersonal skills, in order to help us cope with challenges. It was developed by Dr. Marsha Linehan to treat Borderline Personality Disorder, but has also been proven effective in treating chronic suicidality, and learning mindfulness, and interpersonal skills. A licensed DBT treatment is intensive and requires commitment and practice, and may include one of or both individual and group work as well as frequent and consistent attendance for sessions. It is possible to utilize DBT tools that are applicable to your therapeutic and life goals. This blog is an introduction to DBT tools and how they can be helpful during your therapeutic journey, including opportunities to practice them on your own. If you are interested in more information about implementing these tools, you can call us to schedule a consultation to discuss further, including information about referrals to a DBT program nearest you.

Thinking Dialectically

What does it mean to think ‘Dialectically?’ Simply put, it means holding opposing viewpoints or information about the situation at the same time. You might be thinking, “How is this even possible? Isn’t this confusing or contradictory?”. The idea is to acknowledge the contradictory thoughts and feelings about a situation. Some examples include: starting a new job or position, or getting married. On the surface, these sound like really ‘good’ things to happen. But even changes that we are excited about or look forward to, come with challenges: maybe this new position comes with some risk with the chance of higher rewards. Or, we are marrying the love of our life, but this brings about big changes to our living situation and finances. Part of Dialectical Thinking is about not seeing the situation, or our emotions or thoughts as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’, but as information about our experiences. For example, “I am nervous about having more responsibilities in this new position AND I am excited about the new opportunities, with a new perspective; “This may be challenging, and I can be successful”. Likewise, getting married: “I am excited to be spending my life with the person I love most AND it’s going to be a big adjustment for the both of us”, new perspective: “There will be challenges, and I am still excited for what the future holds”. In other words, we are taking the ‘middle path’ to “Life can be both challenging and fulfilling” or “Life is sometimes difficult, but I can manage”.

Practice: Wise Mind

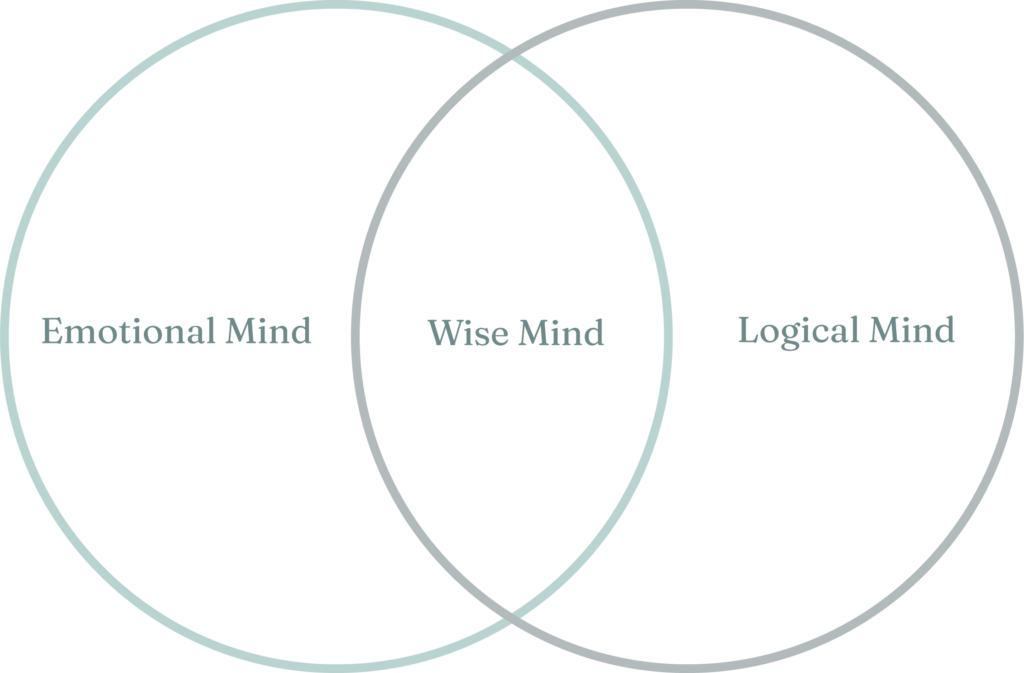

In the Wisemind Venn Diagram, there are 3 sections: On the left, we have Emotional Mind: how we feel about the situation, and how we want to behave according to those feelings. On the right end we have the Logical Mind: the facts of the situation, and how we want to act accordingly. And in the centre, we have Wise Mind: which is about making decisions and acting while honoring our emotions as well as logic.

Example:

- Emotional Mind: My friend said something that really hurt me

- Logical Mind: I’m not sure that they meant to hurt me, and this relationship is important to me

- Wise Mind: I am going to communicate my feelings to this person using “I” Statements because I care about our friendship and I want to address what happened. I may need to use Wise Mind again based on their response.

On a piece of paper or electronic document, organize your Emotional Mind’s thoughts and feelings into one column or section of the document. Do the same for the facts of the situation under Logical Mind. Then, in a third space, write down alternative thoughts and actions that agree with both the Logical and Emotional Mind. Then you will have access to your Wise Mind!

Radical Acceptance

Radical Acceptance is about accepting the facts, and our thoughts and feelings about a situation, and in doing so, our path forward may become more clear. Now, you may be thinking, “How can I accept something that I don’t like”. Radical Acceptance does not force us to like the situation, only to accept the things that are outside of our control, so we can focus our time and energy on healing and the options that are within our control.

For example: Jack’s adult child, Julia, refuses to speak to him, and asks him to give her space without providing details as to why. Jack acts on his feelings of despair and hurt by continuously calling Julia. He thinks to himself, “If I keep calling she will have to pick up eventually and give me answers. Then when I have the answers, I can fix our relationship”. However, Julia does not answer his calls.

Radical Acceptance: Jack can radically accept that Julia does not want to speak to her right now (her words and actions), and to give her the space she asked for. Jack can accept that he does not know why or when Julia will call back, but he can focus on ways to address his own thoughts and feelings in order to decide what to do or say when/if Julia says she is ready.

Practice:

On a piece of paper or electronic document, organize the following in separate sections:

- Facts about the situation (can include, who said and did what, what happened?)

- Your emotions (1 word descriptions ex. Anger, sadness, hurt, etc. If you are having trouble, you can look up a list of emotions to help you)

- Your thoughts (full sentences of what has been on your mind)

- What you can’t change

- What you have control over/what you can change

Melissa M.